This is from the Illustrated London News, 19 August 1967. The comment about the obscure nature of some of Kitaj’s literary references is part-justified, but this post focuses on a Mahler Suite print which links to the far from arcane oeuvre of William Shakespeare.

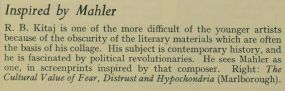

The print is entitled, Let Us Call It Arden/& Live in it! 1966.

Courtesy Tate Gallery

It’s likely that Kitaj was referring to Shakespeare’s As You Like It, one of the best known of his thirteen comedies. The play reflects on the contrast between the way of life and manners as conducted in a city and the milieu of a natural environment, the latter being the Forest of Arden. Shakespeare probably envisaged this on the basis of the Ardennes area of Belgium, (with some overspill into France and Luxembourg.) Alternatively, some scholars have suggested he was thinking more locally – about the Forest of Arden which lay from Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire to Tamworth, Staffordshire.

The notion is that in the city everything is very formulaic, regimented and bound by conventions, while life in the Forest is carefree, allowing people to ‘be’ and express themselves in a way reflective of their ‘true’ self. At a simple level the print could be seen to straightforwardly express this concept, the lower portion filled with busy, disjointedly juxtaposed imagery, with the larger, upper area being quite Rothkoesque. Study tends to return a contemplative (self-centred) experience from the blue/black/grey blocks.

Anticipating the current, apparently disproportionate concern with transgender ‘issues,’ As You Like It features a considerable measure of confusion, stemming from Rosalind disguising herself as a young male, Ganymede. However, the object of her affection is Orlando, so as long as Rosalind remains ‘in drag’, there can be no overt romance. Critics have suggested that Shakespeare was thus reflecting on the fact that city values, though diluted, still had ultimate authority and that the female will in the final analysis always be subordinate to the male.

It may be that Kitaj was simply showing support for the changing societal ethos of the Sixties, in effect advocating a culture in which general hippy values, gender equality, greater sexual freedom/openness and homosexuality flourished.

That’s just a start on evaluating this print and there’s more to ponder, e.g. what is the significance of the Swiss-context lower section imagery? But aside from such considerations, this is another Kitaj print which repays sustained study and provides a very agreeable visual experience.